Finding Neighbors#

Now that you’ve been introduced to the basics of interacting with freud, let’s dive into the central feature of freud: efficiently and flexibly finding neighbors in periodic systems.

Problem Statement#

Neighbor-Based Calculations#

As discussed in the previous section, a central task in many of the computations in freud is finding particles’ neighbors. These calculations typically only involve a limited subset of a particle’s neighbors that are defined as characterizing its local environment. This requirement is analogous to the force calculations typically performed in molecular dynamics simulations, where a cutoff radius is specified beyond which pair forces are assumed to be small enough to neglect. Unlike in simulation, though, many analyses call for different specifications than simply selecting all points within a certain distance.

An important example is the calculation of order parameters, which can help characterize phase transitions. Such parameters can be highly sensitive to the precise way in which neighbors are selected. For instance, if a hard distance cutoff is imposed in finding neighbors for the hexatic order parameter, a particle may only be found to have five neighbors when it actually has six neighbors except the last particle is slightly outside the cutoff radius. To accomodate such differences in a flexible manner, freud allows users to specify neighbors in a variety of ways.

Finding Periodic Neighbors#

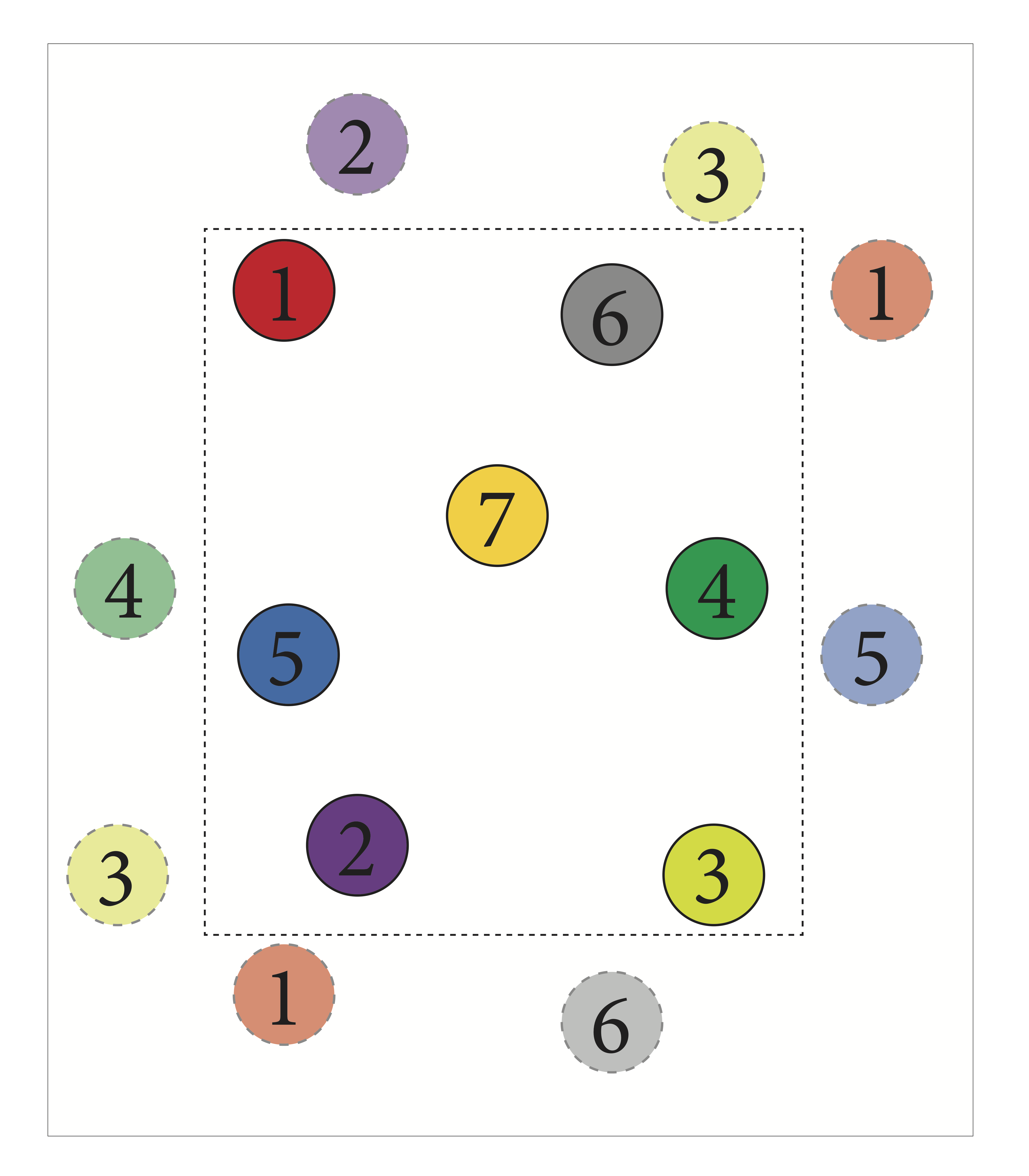

Finding neighbors in periodic systems is significantly more challenging than in aperiodic systems. To illustrate the difference, consider the figure above, where the black dashed line indicates the boundaries of the system. If this system were aperiodic, the three nearest neighbors for point 1 would be points 5, 6, and 7. However, due to periodicity, point 2 is actually closer to point 1 than any of the others if you consider moving straight through the top (or equivalently, the bottom) boundary. Although many tools provide efficient implementations of algorithms for finding neighbors in aperiodic systems, they seldom generalize to periodic systems. Even more rare is the ability to work not just in cubic periodic systems, which are relatively tractable, but in arbitrary triclinic geometries as described in Periodic Boundary Conditions. This is precisely the type of calculation freud is designed for.

Neighbor Querying#

To understand how Compute classes find neighbors in freud, it helps to start by learning about freud’s neighbor finding classes directly.

Note that much more detail on this topic is available in the Query API topic guide; in this section we will restrict ourselves to a higher-level overview.

For our demonstration, we will make use of the freud.locality.AABBQuery class, which implements one fast method for periodic neighbor finding.

The primary mode of interfacing with this class (and other neighbor finding classes) is through the query interface.

import numpy as np

import freud

# As an example, we randomly generate 100 points in a 10x10x10 cubic box.

L = 10

num_points = 100

# We shift all points into the expected range for freud.

points = np.random.rand(num_points, 3)*L - L/2

box = freud.box.Box.cube(L)

aq = freud.locality.AABBQuery(box, points)

# Now we generate a smaller sample of points for which we want to find

# neighbors based on the original set.

query_points = np.random.rand(num_points//10, 3)*L - L/2

distances = []

# Here, we ask for the 4 nearest neighbors of each point in query_points.

for bond in aq.query(query_points, dict(num_neighbors=4)):

# The returned bonds are tuples of the form

# (query_point_index, point_index, distance). For instance, a bond

# (1, 3, 0.2) would indicate that points[3] was one of the 4 nearest

# neighbors for query_points[1], and that they are separated by a

# distance of 0.2

# (i.e. np.linalg.norm(query_points[1] - points[3]) == 2).

distances.append(bond[2])

avg_distance = np.mean(distances)

Let’s dig into this script a little bit.

Our first step is creating a set of 100 points in a cubic box.

Note that the shifting done in the code above could also be accomplished using the Box.wrap method like so: box.wrap(np.random.rand(num_points)*L).

The result would appear different, because if plotted without considering periodicity, the points would range from -L/2 to L/2 rather than from 0 to L.

However, these two sets of points would be equivalent in a periodic system.

We then generate an additional set of query_points and ask for neighbors using the query method.

This function accepts two arguments: a set of points, and a dict of query arguments.

Query arguments are a central concept in freud and represent a complete specification of the set of neighbors to be found.

In general, the most common forms of queries are those requesting either a fixed number of neighbors, as in the example above, or those requesting all neighbors within a specific distance.

For example, if we wanted to rerun the above example but instead find all bonds of length less than or equal to 2, we would simply replace the for loop above with:

for bond in aq.query(query_points, dict(r_max=2)):

distances.append(bond[2])

Query arguments constitute a powerful method for specifying a query request.

Many query arguments may be combined for more specific purposes.

A common use-case is finding all neighbors within a single set of points (i.e. setting query_points = points in the above example).

In this situation, however, it is typically not useful for a point to find itself as a neighbor since it is trivially the closest point to itself and falls within any cutoff radius.

To avoid this, we can use the exclude_ii query argument:

query_points = points

for bond in aq.query(query_points, dict(num_neighbors=4, exclude_ii=True)):

pass

The above example will find the 4 nearest neighbors to each point, excepting the point itself. A complete description of valid query arguments can be found in Query API.

Neighbor Lists#

Query arguments provide a simple but powerful language with which to express neighbor finding logic.

Used in the manner shown above, query can be used to express many calculations in a very natural, Pythonic way.

By itself, though, the API shown above is somewhat restrictive because the output of query is a generator.

If you aren’t familiar with generators, the important thing to know is that they can be looped over, but only once.

Unlike objects like lists, which you can loop over as many times as you like, once you’ve looped over a generator once, you can’t start again from the beginning.

In the examples above, this wasn’t a problem because we simply iterated over the bonds once for a single calculation.

However, in many practical cases we may need to reuse the set of neighbors multiple times.

A simple solution would be to simply to store the bonds into a list as we loop over them.

However, because this is such a common use-case, freud provides its own containers for bonds: the freud.locality.NeighborList.

Queries can easily be used to generate NeighborList objects using their toNeighborList method:

query_result = aq.query(query_points, dict(num_neighbors=4, exclude_ii=True))

nlist = query_result.toNeighborList()

The resulting object provides a persistent container for bond data.

Using NeighborLists, our original example might instead look like this:

import numpy as np

import freud

L = 10

num_points = 100

points = np.random.rand(num_points, 3)*L - L/2

box = freud.box.Box.cube(L)

aq = freud.locality.AABBQuery(box, points)

query_points = np.random.rand(num_points//10, 3)*L - L/2

distances = []

# Here, we ask for the 4 nearest neighbors of each point in query_points.

query_result = aq.query(query_points, dict(num_neighbors=4))

nlist = query_result.toNeighborList()

for (i, j) in nlist:

# Note that we have to wrap the bond vector before taking the norm;

# this is the simplest way to compute distances in a periodic system.

distances.append(np.linalg.norm(box.wrap(query_points[i] - points[j])))

avg_distance = np.mean(distances)

Note that in the above example we looped directly over the nlist and recomputed distances.

However, the query_result contained information about distances: here’s how we access that through the nlist:

assert np.allclose(nlist.distances, distances)

The indices are also accessible through properties, or through a NumPy-like slicing interface:

assert np.all(nlist.query_point_indices == nlist[:, 0])

assert np.all(nlist.point_indices == nlist[:, 1])

Note that the query_points are always in the first column, while the points are in the second column.

freud.locality.NeighborList objects also store other properties; for instance, they may assign different weights to different bonds.

This feature can be used by, for example, freud.order.Steinhardt, which is typically used for calculating Steinhardt order parameters, a standard tool for characterizing crystalline order.

When provided appropriately weighted neighbors, however, the class instead computes Minkowski structure metrics, which are much more sensitive measures that can differentiate a wider array of crystal structures.